April 14, 2022

Class Action Developments in the Circuit Courts

On January 7, 2022, we presented a one-hour PLI CLE titled Trends in Consumer Product Class Actions and Strategies for Settling Them . Following that presentation, we decided to flesh out three Circuit Court class action decisions that illustrate the challenges that come with both prosecuting and defending class actions. What follows is an overview of: (i) the Briseno case, which simply cannot get over the finish line; (ii) the Renfro case, which helps explain puffery through dog food; and (iii) the George case, in which Starbucks had to defend its “best” coffee against claims that some of its Manhattan stores inappropriately use a certain type of “No-Pest Strip” to combat pest infestations. The three cases offer an interesting contrast. In the first, the parties want to resolve it, but for more than ten years have been unable to obtain the court’s blessing. In the latter two, the plaintiffs could not survive the pleading stage. Ah, the joys of class action litigation!

While nowadays consumer product litigation is focused on claims involving vanilla (see here and here and here , among many others), whether a product is truly “non-toxic” (see here and here ), and what makes a product actually recyclable (see here ), in 2011, “natural” claims were all the rage. Included among those was a class action alleging that ConAgra’s product, Wesson Oil, was mislabeled as “100% natural” because it contained GMOs. Briseno v. ConAgra Foods, Inc. , 2:11-cv-05379 (C.D. Cal.). The case’s progress has been measured in years, not months. In 2015, class certification was granted, with the 9th Circuit affirming two years later. 674 F. App’x 654 (9th Cir. 2017). The Supreme Court denied ConAgra’s petition for writ of certiorari. 138 S. Ct. 313 (2017). As you probably suspect, the story does not end there.

In 2017, ConAgra agreed to sell Wesson Oil to the J.M Smucker Company. About two months later, ConAgra, on its own volition, removed the “100% natural” label and stopped marketing Wesson products as “natural.” ConAgra has argued that the litigation played no role in its decisions. Then, in early 2018, the J.M. Smucker transaction fell through, and ConAgra decided to commence settlement negotiations in the Briseno case.

Beginning in June 2018, the parties, with the help of Magistrate Judge Douglas McCormick, started discussing settlement in earnest. Over the following six months, Magistrate Judge McCormick spent approximately 100 hours helping the parties narrow the issues. His approach was sound. First “he helped the parties determine how much ConAgra would agree to pay as relief to the class members.” Dkt. No. 779 at 5. Second, he “helped the parties determine how much Plaintiffs’ attorneys would recover in fees.” Id. On the former, he helped the parties agree to a claims-made settlement that would pay class members $0.15/product for up to 30 units. While $0.15 might seem small, Magistrate Judge McCormick understood that it was “an amount considerably more than the price premium attributed to the ‘100% Natural’ label by Plaintiffs’ own expert.” Id. On the latter, even though plaintiffs’ counsels’ lodestar was more than $10 million, Magistrate Judge McCormick proposed—and the parties accepted—a fee request of $6.85 million, which ConAgra would not oppose (the “clear-sailing provision”). The parties agreed that if the court reduced the attorneys’ fee award, that money would revert to ConAgra (the “reverter clause”). Magistrate Judge McCormick also successfully proposed that the parties value the injunctive relief, i.e., the label change, at $27 million . This would soon get very weird, however, because in December 2018, ConAgra agreed to sell the Wesson Brand to Richardson International. Accordingly, even if ConAgra had wanted to bring back the 100% natural label, it wouldn’t be able to, given that the brand was now owned by another entity. Not to worry: “After the sale, the parties revised the terms of the settlement agreement to clarify that the negotiated injunctive relief would apply to ConAgra only if it reacquired the Wesson Brand .” Id. (emphasis added.).

On April 4, 2019, the district court preliminarily approved the settlement. Following the notice campaign, class members filed a total of 97,880 timely claims for approximately 2.8 million units worth a total maximum payout of $993,919. Six months later, the court granted final approval of the settlement, placing “great weight on the fact that the parties’ agreement had resulted from a court proposal from Magistrate Judge McCormick.” Id. Even though the sought-after attorneys’ fees were roughly seven times the amount the class received, the court approved them, noting that they constituted only half of counsels’ lodestar and reflected the “impressive result achieved given the weakness of Plaintiffs’ case.” In so doing, the court overruled an objector, class member Todd Henderson, who argued that the settlement—with the disproportionate amount of attorneys’ fees, clear-sailing provision, and reverter clause—was unfair and failed to satisfy F.R.C.P. 23(e).

In June 2021, the Ninth Circuit reversed the District Court’s approval order. It held that, even for post-class certification settlements (as this was), F.R.C.P. 23(e) imposes an independent obligation to “ensure that any class settlement is ‘fair, reasonable, and adequate,’” and this obligation includes a review of the attorneys’ fee award to ensure reasonableness. No. 19-56297 (June 1, 2021) at 31. Specifically, the Ninth Circuit found that lower courts must assess whether the Bluetooth red flags—i.e., (1) plaintiffs’ counsel receiving a disproportionate distribution of the settlement; (2) a clear-sailing provision; and (3) a reverter clause—are present, as they will help determine “if collusion may have led to class members being shortchanged.” Id. at 21. Because the ConAgra settlement “managed to run afoul of all three Bluetooth factors” and thus “favor[ed] class counsel and the defendant at the expense of the class members,” the Ninth Circuit remanded the case to the District Court to “give a hard look at the settlement agreement to ensure that the parties [had] not colluded at class members’ expense.” Id. at 24.

On remand, there were a few interesting developments.

First , Magistrate Judge McCormick submitted a declaration describing his role in the settlement negotiations. He offered two critical observations. On the one hand, he “saw nothing in the parties’ conduct before [him] to indicate that they were colluding at the class members’ expense.” Dkt. 739 ¶ 20. On the other hand, with respect to the “court proposals” he made to the parties, he conceded that they did not represent his evaluation of what is the “right outcome”; rather, they represented his “evaluation of the terms that [had] the best chance of being accepted by both sides.” Id. ¶ 14. Critically, he “did not at the time of the negotiations view [his] role as a settlement judge as reaching the issue of whether the settlement should be approved by the Court as fair, reasonable, and adequate.” Id. ¶ 19. This admission would become important later.

Second , the court largely agreed with the objector, Mr. Henderson, who reemerged to ask for discovery into the mediation process. The court allowed Mr. Henderson to obtain “discussions between Plaintiffs and Conagra” as well as “information or material shared with Judge McCormick.” Dkt. No. 750.

Third , in a renewed motion in support of final approval, plaintiffs, despite the Ninth Circuit’s discomfort with the case, asked the district court to grant final approval to the same exact settlement the Ninth Circuit had just remanded, arguing that despite the presence of all three Bluetooth red flags, the record confirmed that there was no “collusion” or “self-dealing.” Dkt. No. 783. This was not to be.

In December 2021, the district court denied plaintiffs’ motion for final approval of the settlement agreement. The court laid out this marker, noting that when all three Bluetooth red flags are present, that is a sign of “possible collusion” but not an automatic basis for settlement rejection. The district court opined, “When they are present, courts must scrutinize the settlement even closer to look for signs that self-interest, even if not purposeful collusion, has seeped its way into the settlement terms.” Dkt. 779 at 12.

Yet, at its core, the court’s conclusion is a bit of conundrum. The court conceded that the settlement was “not the product of collusion in the traditional sense,” i.e., “there is no evidence that class counsel and ConAgra intentionally schemed to enrich themselves at the expense of the class.” But setting that aside, the court focused on what appears to have been the real issue: the lack of proportionality between what the class and class counsel collected. The district court stated, “The fact that attorneys will receive nearly $7 million while the class receives less than $1 million is too disproportionate to ignore. This is particularly true when the structure of the settlement relied on compensating class members based on claims made, but the incentive for making such claims was extremely low.” But the incentive—or lack thereof—was the byproduct of a small-dollar product with an even smaller price premium. If you think about it, the entire situation is like a perfect storm for a settlement that seemingly cannot get over the finish line. But how did this come to be?

For starters, the litigation has been running for more than ten years, with class counsel seeking only 50% of its lodestar. So, class counsel’s fee request already represented a significant haircut over the costs incurred to date. And, as for the value of the claims at issue, the settlement provided the class with more than it could have had it prevailed at trial . But ConAgra repeatedly made clear that it would not allow class members to reap a “windfall.” Dkt. No. 783 at 20. As a result, that the settlement contained a “reverter” clause is no surprise. To the extent the court reduced the attorneys’ fee award, if it went to the class, by definition the class would have reaped a windfall. The same issue would have infected a common fund settlement. Because the per product damages were so small, any sizable common fund settlement would have necessarily resulted in either (1) a windfall to the class; or (2) a large cy pres distribution (that likely would have attracted the same objectors, albeit utilizing a different objection). To make a long story short (or less long), the court’s decision calls into question how class counsel is supposed to resolve a long-running, time-consuming, and expensive class action over a low-dollar product without awarding the class more than it’s entitled to.

Like any good novel, the ConAgra case had an interesting epilogue. In early January 2022, plaintiffs moved the district court to reconsider the order denying final approval, arguing that the court’s denial of final approval was based solely on the amount of attorneys’ fees rather than the benefit to the class. In plaintiffs’ view, because the parties’ settlement agreement expressly granted the court discretion to reduce the attorneys’ fee award, they contend that the court should do just that “as part of approving the settlement.”

Unsurprisingly, the objector, Mr. Henderson, did not agree. Among other arguments, Mr. Henderson chided plaintiffs for failing previously to argue to the trial court that it could reduce the attorneys’ fee to a proportionate amount (whatever that may be), instead choosing “to play chicken with an all-or-nothing strategy.” Dkt. No. 791 at 1. And, as for what an appropriate fee would be—well—Mr. Henderson believed it should be zero. Id. at 9.

On the auspicious 2.22.22, the District Court had what will be, for now, the final word. In denying plaintiffs’ motion, the court clarified that it wasn’t just the disproportion between attorneys’ fees and class recovery that doomed the settlement. Rather, it was the disproportion

taken together with other factors, including the clear sailing provision, the reverter provision, Judge McCormick’s explanation that he considered only what the parties would be likely to accept and not what was fair or just, the likely low claims rate, class counsel’s incentive to make sure claims did not get too high, and the worthless injunction—plus the evidence that the parties actually knew the claims rate would be extremely low and class counsel’s rejection of a more proportional settlement offer—[which] indicated that self-interest infected the negotiations.

Dkt. No. 795 at 7. So, it is back to the drawing board for the parties. Nearly eleven years into litigation and they are still no closer to resolving it.

In February 2022, the Tenth Circuit waded into territory that has bedeviled law students for ages: what is the line between misstatement and puffery? In Renfro v. Champion Petfoods USA, Inc. , No 20-1274, a group of pet owners brought a class action against Champion Petfoods USA, Inc., alleging representations on its Acana and Orijen brands of dog food were false and misleading. Specifically, plaintiffs took issue with the following descriptors:

- •“Trusted Everywhere”

- •“Fresh and Regional Ingredients”

- •“Ingredients We Love [From] People We Trust”

- •“Biologically Appropriate”

Under Colorado law, to prevail on a claim brought under the Colorado Consumer Protection Act, a plaintiff must establish that the defendant made a “ false statement of fact that either induces the recipient to act or has the capacity to deceive the recipient.” Rhino Linings USA, Inc. v. Rocky Mt. Rhino Lining, Inc. , 62 P.3d 142, 144 (Colo. 2003) (emphasis added). On the other hand, “puffery” is used to “characterize those vague generalities that no reasonable person would rely on as assertions of particular facts.” Alpine Bank v. Hubbell , 555 F.3d 1097, 1106 (10th Cir. 2009).

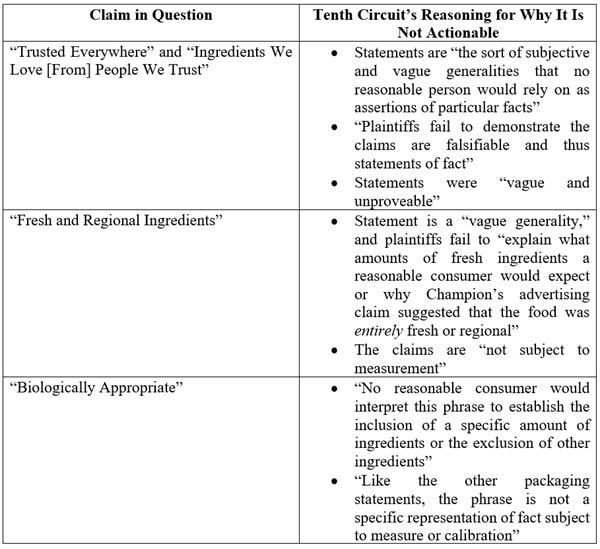

The district court dismissed the claims as either unactionable puffery or overly subjective and thus not materially misleading to a reasonable consumer. The Tenth Circuit affirmed, finding that the statements in question clearly landed on the puffery side of the ledger:

In short, the common thread among the statements at issue is their inability to be measured. “Biologically appropriate” is basically a tautology: the product in question is dog food made for dogs. “Fresh and Regional Ingredients” are ingredients from somewhere (a region) that are largely fresh (and not old). And “Ingredients We Love from People We Trust” is incapable of “testing for falsifiability,” i.e., there is simply no way to know if someone at Champion neither loved some of the ingredients nor trusted the people who manufactured them. When a company’s statements are more general than specific, a 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss may succeed.

Over the past few years, Starbucks has seen its share of litigation, including cases involving: (1) a consumer burning herself after receiving the wrong coffee; (2) claims that vanilla Frappuccinos are made with fake flavoring instead of real vanilla; and (3) allegations that its lattes are underfilled. In 2021, it fended off a different kind of case.

According to a few New York customers, Starbucks’ statements like “Best coffee for the Best You,” “Taste of Inspiration,” “Starbucks or nothing,” and “hear, soul, craft, pride, love[;] you won’t find that in any other cup of coffee” were all misleading because certain Manhattan locations utilized a “No-Pest Strip,” which is a time-release device that emits a powerful pesticide, 2,2-dichlorovinyl dimethyl phosphate (often abbreviated “DDVP”), into the air. George v. Starbucks Corp. , 19-cv-6185 (motion to dismiss decided Nov. 19, 2020). The theory: because these devices are both designed for use only in unoccupied structures and can make you sick (although no plaintiffs complained that they got sick), that Starbucks used them rendered Starbucks’ glossy claims about its coffee and ambience false under New York’s consumer protection laws.

The district court dismissed in full the claims under New York General Business Law Sections 349 and 350, finding that the customers failed to “allege that Starbucks’s advertisements communicate—even indirectly—any specific details about its products.” Id. Further, the court noted that any claim that a seller’s “wares are ‘premium’ or ‘the best’ cannot support a cause of action for deceptive practices, whether made in a single advertisement or a hundred.” Id.

For some reason, plaintiffs here decided to appeal to the Second Circuit, which had very little interest in resuscitating the claims. George v. Starbucks Corp. , 20-4050 (decision Aug. 27, 2021). The Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal, holding that statements like “Best coffee for the Best You” and “Taste of Inspiration” are puffery, i.e., they “vaguely assert that Starbucks’s coffee is better than its competitors in a manner best ‘understood as an expression of the seller’s opinion only.’” Id. They “are not specific enough to ‘misrepresent an inherent quality or characteristic of the defendant’s product.’” Id.

Moreover, the Second Circuit found that while certain statements “were plausibly specific enough to be more than puffery,” they refer “only to how Starbucks sources its products and crafts its coffee and the ingredients it uses in its baked goods. No reasonable consumer would believe that these statements communicate anything about the use of pesticide in Starbucks’s stores .” Id. While the Second Circuit conceded that courts should “ ordinarily refrain from resolving questions of reasonableness on a motion to dismiss,” id. , every rule has an exception. And when the allegations at issue are so disconnected from the allegedly false claims, it simply is “not error” to dismiss those claims. Id.

All in all, another win for Starbucks, and a glimmer of hope for other defendants looking to dispose of mislabeling claims at the pleading stage.

Ross Weiner is the Legal Director at Risk Settlements, where he helps evaluate new business, assess legal and financial risk, and create optimal settlement designs and risk transfer options. Prior to joining Risk Settlements, Ross spent nine years as a litigator at Kirkland & Ellis LLP, where he focused on, among other things, class action disputes. During that time, Ross came to understand the importance of providing clients with creative approaches to settling disputes.

Ezra Church counsels and defends companies in privacy, cybersecurity, and other consumer protection matters. He helps clients manage data security and other crisis incidents and represents them in high-profile privacy and other class actions. Focused particularly on retail, ecommerce, and other consumer-facing firms, his practice is at the forefront of issues such as biometrics, artificial intelligence, location tracking, ad tech, and blockchain. Ezra is a Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP) and co-chair of the firm’s Class Action Working Group.

This article originally appeared on https://plus.pli.edu/Details/Details?fq=id:(350194-ATL10).

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed by the authors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, viewpoints and official policies of Practising Law Institute.

This article is published on PLI PLUS, the online research database of PLI. The entirety of the PLI Press print collection is available on PLI PLUS—including PLI’s authoritative treatises, answer books, course handbooks and transcripts from our original and highly acclaimed CLE programs.

The post Class Action Developments in the Circuit Courts appeared first on Certum Group.

Recent Content